FLIGHT OF FANCY: A GROUNDBRAKING EXHIBITION IN VIENNA

On entering the Bank Austria Kunstforum in Vienna for the exhibition Flying High: Women Artist of Art Brut, visitors are welcomed by the lightly dressed, colorful, muscle-bound figures of Misleidys Castillo Pedroso (*1985). Like fold-out posters from youth magazines, they seem to be attached to the wall with adhesive tape. But, of course, they are framed, counteracting their actual message of being out of place in a gallery or museum setting. But isn't that true of any kind of Art Brut? At least that was true at the time Jean Dubuffet was first thinking about art outside the norms of the art business and conventional production and understanding of art. Since then, the meaning denoted by the term has undergone diverse transformations, even in Dubuffet's own understanding. This kind of artistic expression has long since conquered the white cube and the art historical discourse, as well as the market.

The curators, Ingried Brugger and Hannah Rieger, have succeeded in bringing together a stunning number of masterpieces of well-known, as well as works by almost unknown, but nevertheless quite fascinating, female artists of Art Brut from all over the world – rightly or wrongly subsumed under this term. Particularly noteworthy is the inclusion of numerous mediumistic artists, several of whom were almost completely unknown or have only recently been rediscovered. Undoubtedly, the exhibition is unique in its abundance and quality.

With Pedroso's serene brute force in the foyer, the curators did not intimate the direction of the exhibition, they clearly set it. This exhibition is about vigor (hidden energies), nudity (of the soul above all), and strong art – by women, of course, even if many of them certainly did not feel strong or confident in what they were doing. It is something of a performance show of female outsider art. Nothing is carefully negotiated here; the curators ostentatiously made big efforts in uniting 316 works by 93 artist – to the great benefit of the result.

The first room of the exhibition with the large masterpiece by Aloïse Corbaz Le Cloisonné de théâtre © Photo Nilo Klotz

The first room of the exhibition with the large masterpiece by Aloïse Corbaz Le Cloisonné de théâtre © Photo Nilo Klotz

On entering the first room of the exhibition, the visitor is overwhelmed by the dimensions of the works and the concept. The colossal narrative performance by Aloïse Corbaz Le Cloisonné de théâtre (1950-1951) occupies the entire length of the hall. A fourteen meters long running story, in which the drama of an overwhelming, yet impossible love unfolds dynamically around the central female figure embedded in a visual symphony of symbolic elements. In this high room with its mighty columns and its hieratic impression, other lavish works of blue-eyed couples by Aloïse Corbaz (1886–1964) flank her monumental royal soap opera along the walls like blasphemous church windows. And above all hover what could be prehistoric creatures wrapped in colored wool by Judith Scott (1943–2005) – messengers of unknown myths and stories from a time before time. Magic objects of a sunken civilization from the abysses of the soul. Somewhat skeptical, but vigilant the Nanotyrannus of Julia Krause-Harder (*1973) appears to observe the spectacle around him. Here everything seems united in a comprehensive framework of myths, cosmology, and evolution as manifestations of images of the dramas unfolding in obscure places of the individual psyche. It was that, what Ludwig Klages had whispered about when he swaggered in his On Cosmogonic Eros:

The soul is the meaning of the living body, and the image of the body is the manifestation of the soul. Whatever appears has a meaning; and every meaning reveals itself as it manifests. Meaning is experienced internally, the manifestation externally. The first must become an image if it is to communicate itself, and the image must be re-internalized again so that it may take effect. [1]

It is this that the visitor gets to see in this exhibition: Images of the body, which are images of the soul, which are just "images".

Installation view with works by Anna Zemanková and Emma Kunz © Photo Nilo Klotz

Installation view with works by Anna Zemanková and Emma Kunz © Photo Nilo Klotz

The women who, out of an inner urge, created these most diverse works of art, often remained unknown or were misjudged. Many of them produced their artistic output in self-imposed seclusion, not few were patients in psychiatric institutions, others worked in collaboration with unseen entities. Sometimes they created tiny miniatures of disturbing peculiarity or enchanting beauty. At other times it seems that even the largest sheets of paper would not suffice to adequately capture the incessant creative power of the inner cosmos, which demands expression. Madge Gill (1882–1961) was one who knew how to master both formats with an abundance of dense lines covering the surfaces in elegant compositions with remarkable confidence. Under the influence of her spirit guide, she not only left behind countless postcards, but also colossal works on calico.

Several of her sized works are on display in a large hall. They seem like tapestries lining the walls of a castle from another dimension, as if she had made visible the shades, lemurs, spirits, and ghosts that populate the carceri of Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Gill’s works are placed close to the small drawings of Jeanne Tripier (1869–1944), the self-proclaimed “médium de première necessité”, the emissary of Jean d'Arc, in which inkblots applied in a targeted manner and in many layers combined with inspired writing provides the fertile ground for pareidolic illusions and prophetic imagery.

On the walls of this room, dedicated to the Collection de l'Art Brut founded by Jean Dubuffet, a whole series of mediumistic artists enter into dialogue with one another. To me, the room appeared filled with whispering voices emanating from the volutes and tendrils of Jane Ruffié (1887–ca. 1963) as if they were strange speaking tubes, answered by Henriette Zéphir's (1920–2012) spirited hiss from her colorful cascades of energy, the deep and solemn sounds emitted from the claustrophobic worlds of Jeanne Tripier and Madge Gill being responded to by the otherworldly chants of Magalí Herrera's (1914–1992) vibrating cosmic-organic eruptions.

Didactically, the exhibition follows the great collections. In addition to the Collection de l'Art Brut, there were rooms for the L'Aracine Collection of the Lille Métropole Museum of Modern Art, Contemporary Art, and Art Brut and the important collections of psychiatric material such as the Prinzhorn Collection, the Morgenthaler Collection and the Gugging Collection.

Mediumistic works by Marguerite Burnat-Provins, Clara Schuff, Gertrude Honzatko-Mediz, Nina Karasek, Mme. Favre,Helen Butler Wells, Agatha Wojciechowsky © Photo Nilo Klotz

Mediumistic works by Marguerite Burnat-Provins, Clara Schuff, Gertrude Honzatko-Mediz, Nina Karasek, Mme. Favre,Helen Butler Wells, Agatha Wojciechowsky © Photo Nilo Klotz

Mediumistic art is prominently represented with works by so far little-known female artists such as Gertrude Honzatko-Mediz (1893–1975), Nina Karasek (1883–1952), Alma Rumball (1902–1980) and Clara Schuff (1893–1987). In addition to the works of more well-known mediumistic artists, such as Anna Zemanková (1908–1986, in her case however the attribution of “mediumistic art” is somewhat questionable), Mme. Favre (19th cent.), Josefa Tolrà (1880–1959), Margarethe Held (1894–1981), Helen Butler Wells (1845–1940), Marguerite Burnat-Provins (1872–1952), Emma Kunz (1892–1963), and Agatha Wojciechowsky (1896–1986), this group of works above all provides an impression of the stunning variety and range of artistic expression inherent in mediumistic art.

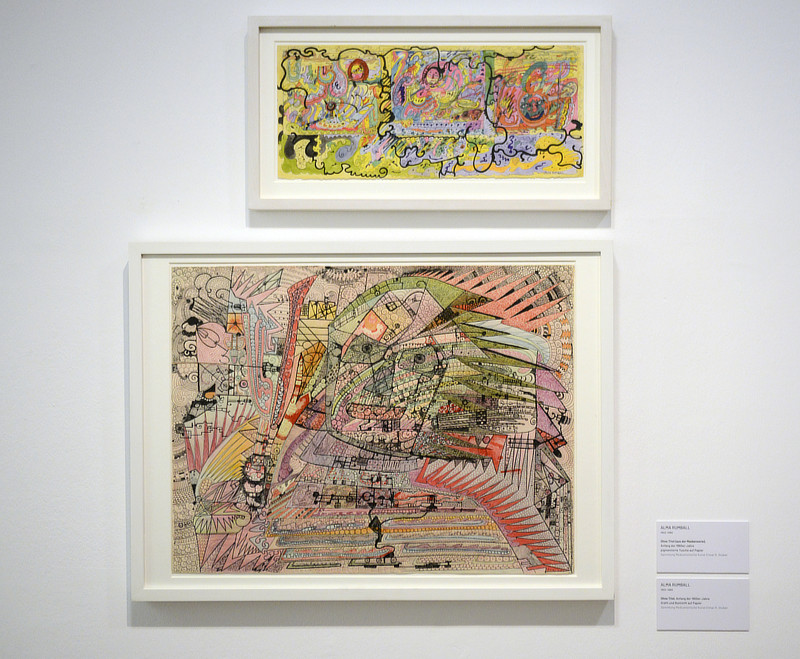

Two works by Alma Rumball © Photo Elmar R. Gruber

Two works by Alma Rumball © Photo Elmar R. Gruber

In works of mediumistic art, a transpersonal dimension becomes translucent, which at times is expressed in “symbolist” and “surreal” or “abstract” compositions avant la lettre of peculiar suggestive power. It is possible to feel this presence of something that transcends the purely individual mode of expression by allowing oneself to follow the labyrinthine paths into fairytale territories mapped by Alma Rumball, or monitor the feather-light beings of Clara Schuff, who transport hieroglyphics from sunken or non-earthly civilizations, fleetingly and gossamer like the flap of an angel's wings. Or if one were to immerse oneself in the somber intermediate realm of Gertrude Honzatko-Mediz, the inconceivable region where osmosis takes place between the living and the dead, or if one were to lift off through the spherical gates of Nina Karasek into her otherworldly realms of light, with her hand guided by none less than Leonardo himself. Then it could be that the spectator would begin to get an impression of what flying high might have meant for these artists.

[1] Ludwig Klages, Vom kosmogonischen Eros, Stuttgart: Günther, 1951, p. 63.

© 2019 Elmar R. Gruber